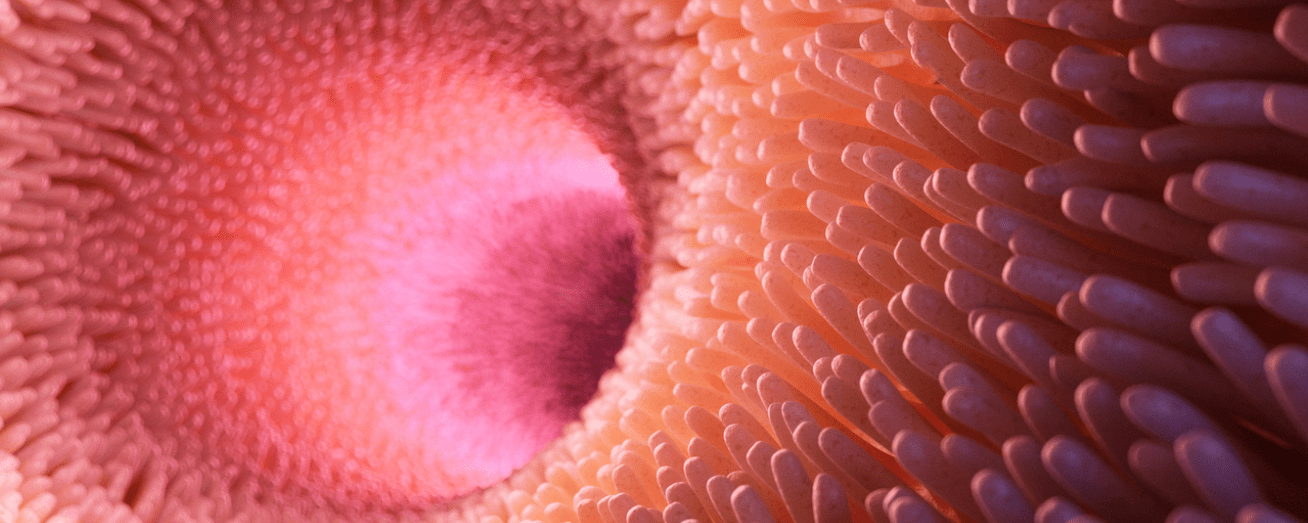

For the majority of patients with celiac disease (CeD), a lifelong gluten-free diet (GFD) leads to symptom improvement, intestinal healing and avoidance of long-term complications. However, despite a GFD, a subset of patients may experience persistent villous atrophy (pVA).

pVA is generally defined as Marsh ≥ 3a or partial villous atrophy that persists 2-3 years or more following transition to a GFD, though exact definitions vary slightly in research and in practice. pVA can be due to poor dietary adherence to a GFD, slow responsiveness following gluten elimination, hypersensitivity to gluten or, in rare cases, premalignant or malignant complications of CeD [1].

Concerns of Persistent Villous Atrophy

The literature on the relationship between pVA and long-term outcomes in CD is mixed and sparse [2]. The clinical profile of patients with pVA is also poorly defined. There is little research on the clinical phenotype of patients who develop pVA for clinicians to use to guide identification of those at higher risk who would benefit from closer monitoring and follow-up [3].

Duodenal histology, though invasive, remains the gold standard for evaluating response to a GFD in CeD [4]. After initial CeD diagnosis, follow-up duodenal biopsy is not always performed to assess mucosal healing and there are few reliable, less-invasive methods to monitor intestinal rehabilitation. When clinical response to a GFD is poor, histological reassessment is recommended to assess for pVA. Many patients may also remain asymptomatic, despite pVA [5].

New Findings on Risks of Persistent Villous Atrophy

Recent research evaluated the potential association between pVA and risk for other health complications and mortality. It also investigated clinical predictors of pVA to develop and validate a tool to identify CeD patients at high risk for pVA.

Findings provide a clearer picture on the estimated prevalence of pVA, which may be as high as 23% [2]. The strongest predictor of pVA was poor adherence to a GFD, though slow responsiveness to a GFD also played a role. Risk factors associated with pVA also included classical CeD symptoms and diagnosis after 45 years old. These characteristics were used as predictors to develop and validate a 5-point scale to identify patients at risk for pVA based on age at diagnosis (≥ 45 years), classical pattern of CeD, lack of clinical response to GFD and poor GFD adherence [2].

Findings also show that pVA is associated with increased risk for health complications and mortality. Risks of pVA are likely related to chronic inflammation, which in turn can lead to long-term tissue damage. In this study, 21% of patients with pVA were diagnosed with complications of CeD, including type 1 and type 2 diabetes, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and esophageal cancer [2].

Among the population studied, 34.1% also had ongoing symptoms at follow-up 32 months following diagnosis. The researchers suggest that follow-up biopsy at 32 months may provide a clearer picture on mucosal healing, as the standard 1-2 year window commonly used in previous studies may not provide sufficient time for full mucosal recovery and lead to an incomplete picture on prevalence of pVA [2].

Clinical Implications

While previous research had shown an association between pVA and increased risk for lymphoproliferative disorders and compromised bone health, this research provides richer insight into other health complications that may be associated with pVA. Though researchers note that variations in disease severity and differences in populations who underwent a follow-up biopsy may have influenced these differences in observed risk in prior studies, the prevalence and risk of pVA is far clearer.

The association between health complications and mortality associated with pVA also points towards the importance of personalized follow-ups to assess mucosal healing. The new validated scoring tool can enable earlier identification of patients with CeD at the highest risk of pVA who may benefit most from targeted interventions to reduce risk for long-term consequences. Such scores can guide personalized follow-ups and monitoring plans. A repeat duodenal biopsy can also be considered in patients with the highest risk score, rather than based on symptoms alone.

Lastly, the presence of poor GFD adherence and its strong association with pVA also emphasizes the importance of dietary support to ensure proper implementation and adherence to a GFD as a means to avoid pVA. Overall, these findings underline that prioritization of deep mucosal healing is important and significantly impacts disease progression and long-term outcomes and provides practical guidance for clinicians to reduce risk for pVA-associated complications.

References

- Fernández-Bañares F, Beltrán B, Salas A, et al. Persistent Villous Atrophy in De Novo Adult Patients With Celiac Disease and Strict Control of Gluten-Free Diet Adherence: A Multicenter Prospective Study (CADER Study). Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(5):1036-1043. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001139

- Schiepatti A, Maimaris S, Raju SA, et al. Persistent villous atrophy predicts development of complications and mortality in adult patients with coeliac disease: a multicentre longitudinal cohort study and development of a score to identify high-risk patients. Gut. 2023;72(11):2095-2102. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329751

- Lebwohl B, Murray JA, Rubio-Tapia A, Green PH, Ludvigsson JF. Predictors of persistent villous atrophy in coeliac disease: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(5):488-495. doi:10.1111/apt.12621

- Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):656-677. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.79

- Kaukinen K, Peräaho M, Lindfors K, et al. Persistent small bowel mucosal villous atrophy without symptoms in coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(10):1237-1245. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03311.x